Leviticus: how to be holy

You could sum up the book of Leviticus with God’s repeated command: “Be holy, as I am holy.”

This book is filled with details on how the people of God should live, eat, sacrifice, celebrate, and more. (We’ll get into why Israel needed this kind of direction in a moment.)

The name “Leviticus” refers to the many laws for the priests, all of whom belonged to the tribe of Levi. If you know much about the twelve tribes of Israel, you know that Levi is kind of an oddball in the bunch (more on that here).

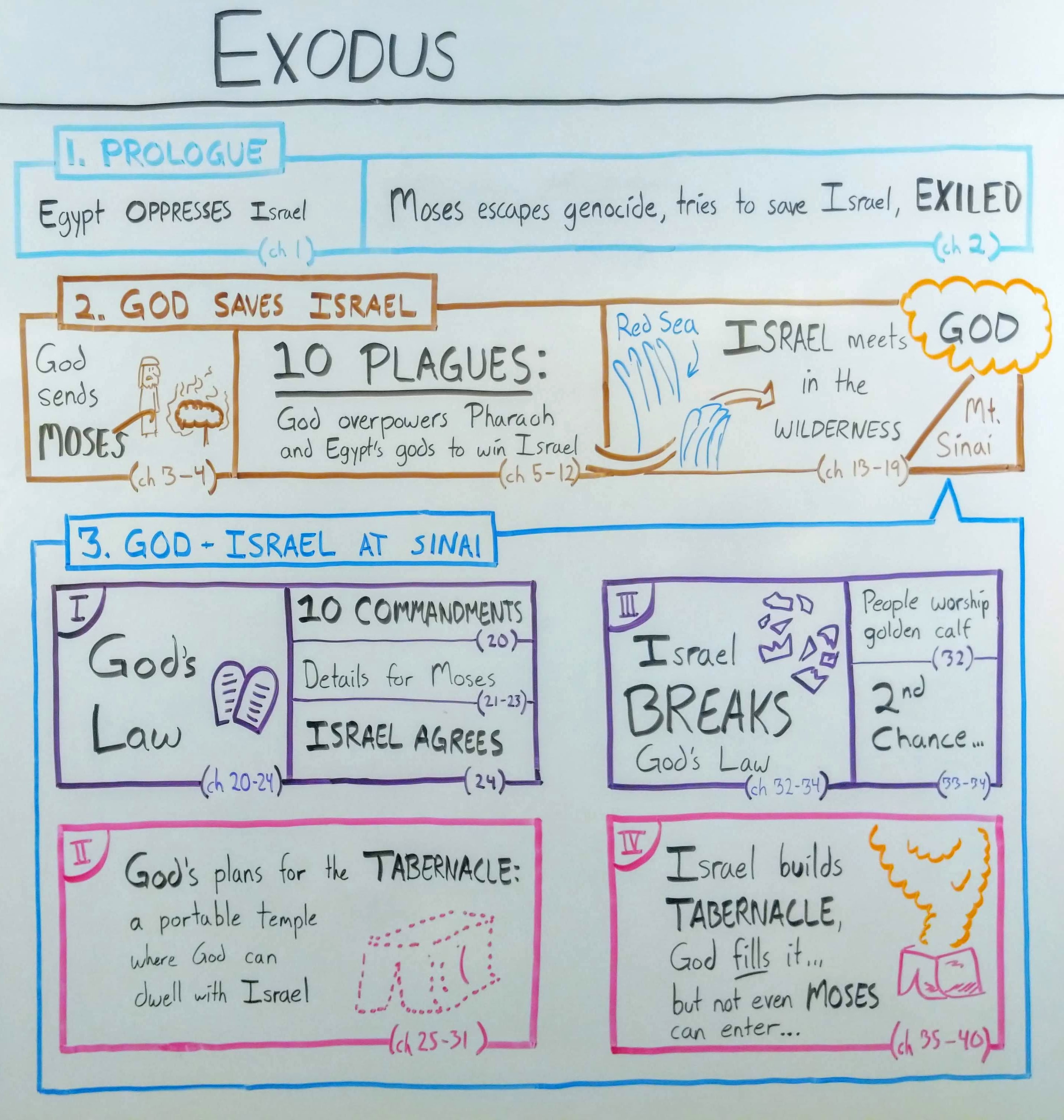

Leviticus is the third movement in the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses), and picks up where Exodus leaves off. The children of Israel have just built a tabernacle, a temporary temple where God can dwell among them as they journey through the wilderness.

Now the Lord is relaying specific laws through Moses to His people. There’s very little narrative in the book of Leviticus, but a few important things happen, such as Aaron’s ordination and the deaths of Aaron’s sons. The story of Israel’s journey to the promised land picks back up in the book of Numbers.

Important characters in Leviticus

God (Yahweh)—This isn’t a cop-out. This whole book is about how the nation of Israel needs to live in order to survive living in the presence of such a powerful, holy being.

Moses—He led the Israelites from Egypt to Sinai. At this point in the story, Moses has already passed along many, many laws to the people of Israel on God’s behalf. In Leviticus, Moses continues to list the ways Israel can stay pure enough to live alongside their God.

Aaron—Moses’ older brother and the high priest of Israel, Aaron is a character to keep an eye on throughout the Pentateuch. Leviticus’s narrative elements have a lot to do with Aaron. In this book, Aaron is consecrated as the high priest, but this is also the book in which God kills Aaron’s sons.

Key themes in Leviticus

I like to find a passage in each book of the Bible that sums up what that book is all about. Moses makes it easy for me:

“Thus you are to be holy to Me, for I the LORD am holy; and I have set you apart from the peoples to be Mine.” (Le 20:26)

You can see a piece of art for each book of the Bible here.

Holiness

“Holy” means “set apart”—but it’s a lot more involved than just being special. God is holy: far greater in love, goodness, power, and justice than humans. Until this point in the Bible, God has been a long way off from the people of earth. Although God has communicated with humans and in some cases even appeared to them privately (think Abraham’s visitors in Genesis 18), he has yet to publicly manifest his presence on earth since the garden of Eden.

But all this has changed. God has made Israel his people: a people that now represent him on earth. He has now established his presence in the tabernacle, a portable holy place where God can dwell in the midst of his new nation.

But if people are going to live in the presence of God, some things will need to change. Because God is so “other” from the world, the people associated with him must become “others” too. God is holy, and his people need to be holy as well.

Cleanliness and uncleanliness

One way that the ancients understood holiness was in terms of whether something was “clean” or “unclean.” This isn’t the same as “good” or “bad.” It’s a sense of purity. Is something aligned with the god we are approaching? Or is it unaligned?

This wasn’t specific to the people of Israel. People of most religions (past and present) have an understanding that there are ways that are appropriate and inappropriate when it comes to interacting with the divine. Those who work and live closest to a divine being are expected to abide by more stringent rules. The rules vary from religion to religion. We even see this within Christianity today: some faith traditions prefer married church leaders, others prefer celibate leaders.

This is a core theme to the book of Leviticus. When someone is operating in alignment with God’s purity laws, they are “clean.” When someone is out of bounds, they are “unclean.” The book of Leviticus has a lot to say about how to stay clean and how to become clean again.

An important thing to note: throughout the Pentateuch, Moses assumes that everyone will be unclean at some point. After all, everybody poops (Dt 23:12–14). The point is to live in a manner that respects the presence of God.

Zooming out: Leviticus in context

Leviticus is right in the middle of the Torah, the first five books of the Bible. It has a reputation for being boring, harsh, and unpopular. (But it’s not the least-popular book of the Bible.)

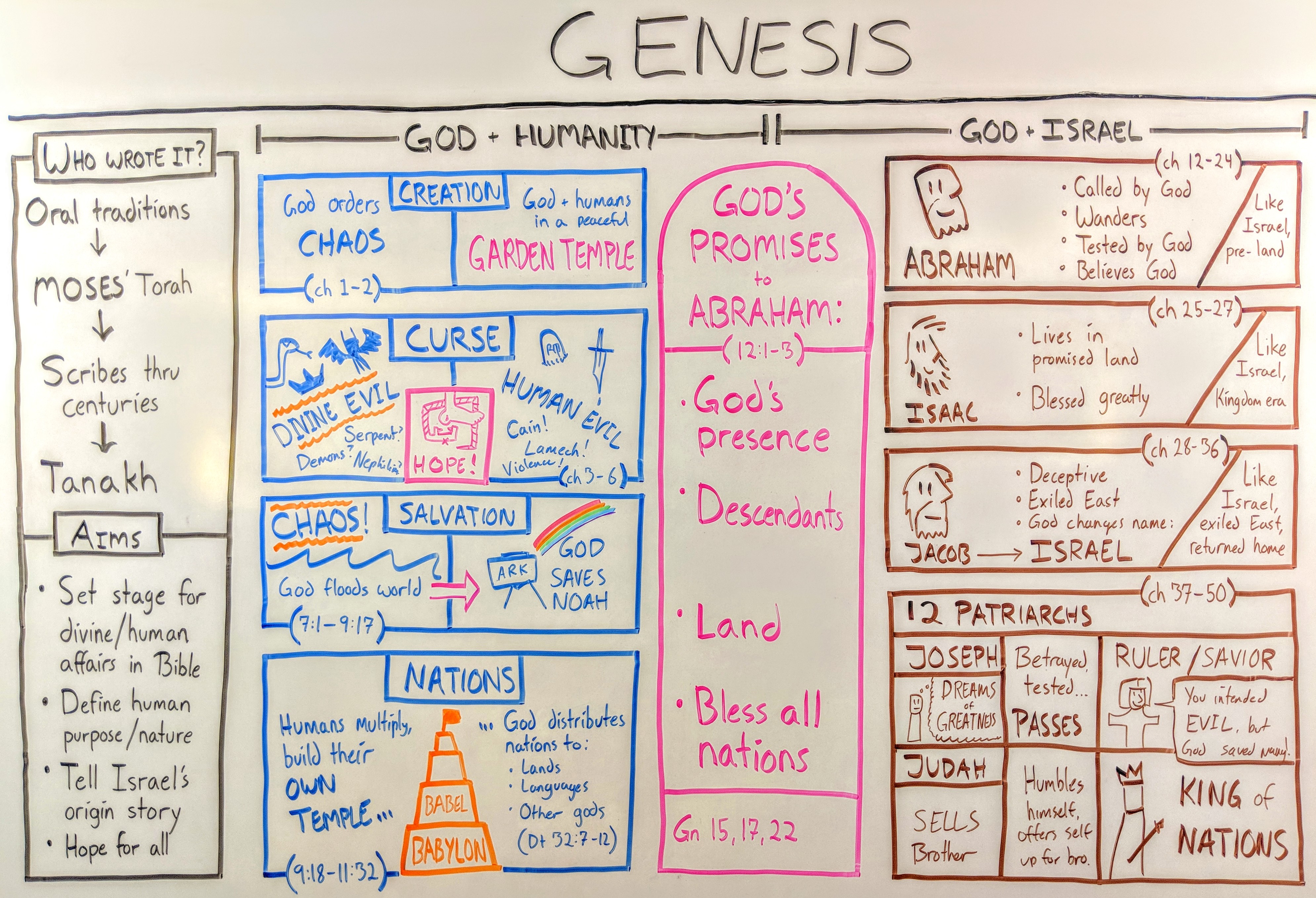

In Genesis, we saw Israel’s origin story. At the tower of Babel, God and the other divine beings scattered the families of the world into nations with their own languages. A few generations later, God chooses Abraham as the patriarch of his own special nation.

In Exodus, Abraham’s descendants have multiplied, becoming a mighty people group cohabitating with the Egyptians. The Pharaoh enslaves the people for a few centuries until God rescues them. After a dramatic exit from Egypt, God makes a special agreement with Israel, making them his people and himself their only God. The people then build a tabernacle, and the Creator of the world begins dwelling among his people.

That’s why Leviticus is so important. It’s a new normal: Yahweh is publicly living with humans. This hasn’t happened since the Garden of Eden, when God would visit with Adam and Eve. Last time God shared a place with humans, the humans (with help from an evil serpent) messed it up. How can they get it right this time?

Not a lot of story happens in Leviticus. The people stay camped at Mount Sinai throughout the book. It’s not until the book of Numbers that they resume their journey to the promised land—and that journey isn’t completed until the book of Joshua.

Leviticus’ role in the Bible

Leviticus is about holiness (being set apart, separate)—both God’s holiness and the holiness He expects of His people.

Whereas Exodus displays God’s holiness on a cosmic scale (sending plagues on Egypt, parting the Red Sea, etc.), Leviticus shows us the holiness of God in fine detail. God spells out His expectations for His priests and people so that the congregation can appropriately worship and dwell with Him.

The call to holiness in Leviticus resounds throughout Scripture, both the Old and New Testaments. Parts of the Levitical law are fulfilled in Jesus Christ, such as distinctions between clean and unclean foods (Mark 7:18–19), but the call to holiness still stands—Peter even cites Leviticus when he encourages us to be holy in all our behavior (1 Peter 1:15–16).

Quick outline of Leviticus

- How to give offerings (Leviticus 1–7)

- Aaron and sons ordained (Leviticus 8–10)

- Cleanliness laws for the congregation (Leviticus 11–15)

- Atonement for sin (Leviticus 16–17)

- How to be a holy culture (Leviticus 18–27)

Who wrote Leviticus?

The whole Torah is a carefully, intentionally edited work. Moses is traditionally credited as the human author of the Old-Testament book of Leviticus. This is because Leviticus is part of the Torah, which is known as the Law of Moses.

The whole Torah is a carefully, intentionally edited work. Moses is traditionally credited as the human author of the Old-Testament book of Leviticus. This is because Leviticus is part of the Torah, which is known as the Law of Moses.

That doesn’t necessarily mean Moses penned every single word of this book. However, Moses is the main human character in these books, and since Moses is the one receiving directives from God, the books are usually attributed to him.